Katwe, a genuine pleasure

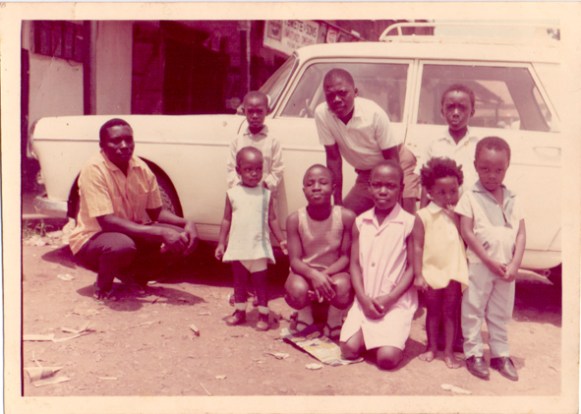

This was a grey Datsun Nissan Pickup truck, registration UYU 066. My Dad got this much later to fetch food from the farm on Jinja Road and take us back to various boarding schools. The moment in the picture was taken at Katwe on our way home to Makindye from the farm. This car’s family name was Kaddangadi.

By Annette Sebba

These and many more memories have been triggered by the 2016 Uganda movie, Queen of Katwe. I agree with Olly Richards of the Sunday Times, United Kingdom, that even with a clearly signposted ending, the movie still manages to offer surprises. Nair delights in Uganda, painting a country of many social contrasts and cultures to embrace possibility, and not poverty. Katwe, since 1962, has been a center of African ingenuity, where artisans, craftsmen, and technicians repair imported products, improve them, or make imitations of the original articles using what the Baganda call Magezi ga Baganda (Wisdom of the Baganda). Some of the good and fun things we had growing up have disappeared, changed, or been replaced over the years. Boda bodas, striped taxis, traffic jams, floods, telecom providers, mobile phones, hair salons, hawkers, aluminum saucepans, kaveeras (plastic bags), rolex chapattis, potato chips, and brick making are evidently current phenomena. The railway line, prostitution, gourds, charcoal, maize, mulondo, matooke, gonja, tadoobas, kangas, rosaries, and then that finger slapping remain Katwe’s Cool Cats identities I can remember very well.

The Railway Line

When I was growing up, it was taboo to go near or walk along the railway line. We would only get a glimpse of it when going to school over the flyover (ettaawo ly’akatimba). People we considered brave, walked on the railway line bringing back some of those black stones that many women used as knife sharpeners. The railway line had shiny black stones in between the metal tracks running into a thin line that disappeared into the distance. As a child living in Katwe between 1977 and 1978, it was a reward to get out every evening from the back of the shop and see the train with its endless set of carriages chugging away. I remember it as enthralling and giving us great joy. That joy was the reason why my siblings and I always fought amongst ourselves to take out the rubbish on hearing the train’s warning horn.

The People

Another fascinating moment that we used to enjoy was to see the President’s motorcade passing along Katwe road. Idi Amin Dada, the then president, would sometimes get out of his Mercedes Benz or Jeep and greet people standing by the roadside. Amin was always smartly dressed in a Kaunda suit or army uniform.

There was a community center at the Katwe Martyrs Church teaching secretarial classes and handicrafts. In fact, I took secretarial classes there during my senior four vacation. Most of our relatives were Christian. Some had rosaries around their necks but no one had ever explained to me that the rosary-wearing ones were Catholic. Our neighborhood was predominantly Muslim. It was advantageous to be Muslim during the Amin years. Many people converted to Islam. The army recruited from the Moslem community, as well as ethnic groups in the West Nile area bordering South Sudan like the Kakwa. Access to government services and opportunities was easier attained through belonging to the right religion or ethnicity.

The Food

There was, and still is, a food market in Katwe. We lived just opposite this market though I have very little memory of ever being inside it. There were strict rules of access: bicycles and children were not permitted. Later, the Central Province Governor, Nassur Abdullah, whose conviction was to keep the Central Province clean and crime free, forbade walking into the market dressed in sandals. Non-compliance meant that his henchmen would make the lawbreaker eat the sandals. In addition to that, at the market entrance was a madman called Semuwemba. His dirty, tangled long ropes of hair and beard scared most children. There were rumors that he was a government spy because he would disappear for several days then return to the same spot. My favorite food was fried Irish potatoes that we had for breakfast before going to church at Martyr’s Church, Katwe every Sunday.

The Vehicles

The few vehicles that could be seen parked along Kayemba Road belonged to reputable people in the neighborhood. One of them was Hajji Nkolabutaala who owned a grey Ford Anglia. He would drive to the city from Butambala to supply tadoobas (little paraffin lamps) to market vendors. There was also Kewerimidde’s light blue Volkswagen. Kewerimidde was a hair salon owner remembered for her exquisite styling and stunning rental wedding dresses. Kyapa Mbalasi’s Volkswagen Kombi Van was a transport vehicle where he transported and sold Kyapa Mbalasi, that famous Ugandan balm remedy for colds, headaches, and many other ailments. Others included Hajji Bedi’s white Toyota Pickup, and Mr. Kaleeba’s black Toyota Pickup which transported fish from Lake Victoria to city markets. Businessmen Mr. Bwete, Mr. Kaggwa and Mr. Kakooza owned white Toyota Pickup trucks. All these were new and well maintained cars. I used to think that only Muslims could own cars until the day my Dad drove home in a 305 Peugeot increasing the number of cars on Kayemba road for a few months before the soldiers drove it away.

The Terrors and Horrors

Our Peugeot then belonged to an army officer who would drive it back to Katwe several times but someone had warned my Dad that the soldiers were looking for the previous owner. So he never said a word or made the slightest attempt to claim it. In those days, people would disappear or be taken away by soldiers with no warning and no charge. Even though we were young, engaged in our games, we could feel that sense of terror and fear around us. Soldiers would walk into any home, shop, or market, and walk away with any valuables their eyes landed on including women or girls. They were most interested in wrist watches, radio cassettes, television sets, cars, money, cigarettes, sofas, any imported items or anything that appeared expensive.

I have very sad memories of a particular day that changed our lives. It was September 9, 1977. President Amin signed the death warrant by firing squad of fifteen men at Pan African Square on Queensway, Entebbe Road, in the area known as Kalitunsi. The previous day, and that every morning, loud speakers on trucks moved around the city calling on the public to turn up and witness the execution. My Dad closed the shop that entire day although I doubt he turned up at Kalitunsi. The following day, the shop remained closed for half the day. Roads were deserted. That morning my Dad contacted his friend, Mr. Muwanga living in Makindye, to find him land to build a house. That marked our exit from our home in Katwe. The shop remained active and it is still there. Not to attract attention, my Dad never bought another car. He rode a bicycle to work and back home to Makindye in the evening.

Katwe was no longer a safe place to live. There were too many robberies, black market deals, alcohol, drugs, and bayaaye (hooliganism).

We kept a dog named Kali. The name originated from a brand of smuggled cigarettes from Kenya sold only on the black market. One day, my younger brother was alone at the shop counter when three soldiers walked into the shop requesting for Kali. My brother was so excited to serve customers in the army uniform. He took them to the dog’s kennel. Upon opening the door, Kali pounced on one of them. By the time my Dad got there the long list of demands for the assault was a penalty he gladly paid. It was far better than prison. This is probably why we children stayed at the back of the shop.

The tunnel below the Queensway road was another place we had fun walking through to visit my Aunt who lived in Nkere Zone. It was cool, lit with yellowish lights, and little water channels on either side. It was not as crowded as it is today, so we could play there. Katwe is a swamp; you could literally dig a well anywhere. My Aunt kept a tortoise in the pond in front of her home. We loved to watch its slow movements. We would play wire car races and dodge ball in her big compound. I only wondered why my Dad did not dig a well at our house to cut down on the big water bills since I often amused myself by opening and watching the tap water flow. I was a kid!

Katwe currently offers fresh challenges, and like Phiona’s maneuvers on the board game in the movie Queen of Katwe, one definitely must have a pocketful of strategies to survive there. The girls often opt for prostitution; boys go into betting, drugs and crime with no desire to go to school. Many live in pain because there is no medicine at the clinics, while others live in constant fear and deceptions when they default on rent or merciless money lenders. Life squeezes some people until they have nowhere to go. Even when victory dares show her face in this place, she arrives empty handed: no money, fame, redemption, or happiness. If one of these comes, they stay only a short while. Where is the clear path to freedom?

All images courtesy of the author, Annette Sebba.